Photo by Nina Subin[/caption]

In honor of International Women’s Day on Thursday, March 8, we recently sat down with Liza Mundy, a journalist and author who specializes in the role of women in the workforce. A former reporter for The Washington Post, Mundy has written four books, including a bestselling biography of Michelle Obama.

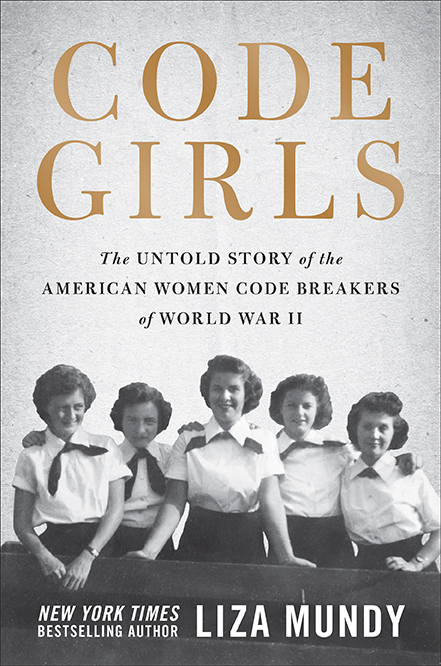

Code Girls, her most recent book, was published in October 2017 and tells the story of the unsung heroes of World War II—thousands of women who worked as codebreakers in the U.S. Army and Navy and who helped crack Japanese crypto systems.

While that gave the United States an advantage during the pivotal Battle of Midway, the women responsible were effectively muzzled, and, until Mundy came along, never recognized for their accomplishments. That book, plus her groundbreaking piece in The Atlantic early last year, “Why Is Silicon Valley So Awful to Women,” made us want to chat more with her about her perceptions of women in technology.

Listen here or read the transcript below.

Let’s start with Code Girls. What’s the story, and what got you interested in this?

The story is about World War II, and it’s about more than 10,000 women who were secretly recruited by the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy to come to Washington to learn how to break codes. It’s about how the work that they did clearly helped us win World War II.

We had a bigger code-breaking operation than Bletchley Park, although Bletchley Park was more famous because it’s more glamorous. But we actually had thousands and thousands of code-breakers, and we had sole responsibility for the Pacific Ocean and all the Japanese code systems that were being used. It was primarily women who were doing the work—but they were sworn to secrecy during the war and afterwards, so they kept the secret. And most of them took the secret to their graves.

I learned a little bit about this story, and then I went out to the National Security Agency. I talked to the agency historians, and they related some more of the story to me. Then I spent about three years tracking down living women and got documents declassified, and going through files at the National Archives.

That’s amazing. What did you learn in writing the book?

I learned that 10,000 women secretly broke codes during World War II—I mean, it’s like a companion story to Hidden Figures. Those, obviously, were women; female African-American mathematicians working for NASA powering the space race. These women came a little bit earlier, but it’s a similar story about women playing an instrumental role in a global war and not getting any credit for it.

Why do you think it took until now for the story to be told?

Because the women kept the secret—they were told during the war that if anybody asked them what they did they were to say that they were secretaries, that they sharpened pencils, and filled ink bottles, and emptied waste baskets. People believed them because they were women, so people believed that the work they were doing couldn’t possibly be important. In that sense they were the ideal intelligence officers.

This was intelligence that they were doing, it was also decryption, literally. It was decryption and cyber-security and hacking.

By the time histories and memoirs began to be written about World War II code breaking—books like The Imitation Game and any number of books, really thick books, about specific codebreaking, about the [Battle of] Midway—historians really neglected the women’s role.

In some of the books that I read, it would literally be mentioned in a parenthetical by a male historian: “Oh by the way, most of this work was done by women.” But they would make the assumption that the important work was actually being done by the men…

So you’re an expert on women at work. Where did 2017 leave us in this narrative?

I think one of the reasons that we’re still having these absurd conversations about whether women belong in the tech sector is because these secrets were kept and because women were written out of the history.

I mean, so much of our tech sector was born during World War II; the early computers that the army and the navy developed, which were our first computers, were developed to break codes or to calculate weapons’ trajectory. So the Army was working on ENIAC, the Navy was working on the Mark I computers that Grace Hopper was instrumental on working on. And the ENIAC was programmed by women.

All these women were being competed for during the war, but because their contributions were written out of history for so long, we still find ourselves arguing with people like James Damore over whether women are as well-suited as men to do this work, when, in fact, the field was pioneered by women. And then after the war, when it became clear that it was going to be huge and profitable, women were sent back home.

You wrote The Atlantic story “Why is Silicon Valley so Awful to Women” around the same time that Susan Fowler threw this topic wide open. Did you have any indication when you were writing that story that it was gonna become this huge?

That broke literally as my piece was going to press, and we were able to work in a reference to it in the printed piece, and then a bit more in the online version of the piece. But looking back at some of the reporting I did, and some of the women that I interviewed—specifically women involved in venture capital—and talking about the sexism and sexual harassment that they encountered, I put two and two together and realized that they were talking about the venture capitalists who were named and accused of sexual harassment not that long after the Susan Fowler memo.

What do you think are the trends we’ll face this year in terms of women at work? And what are some challenges?

Well, it sounds cliché to say this has been a watershed year. I mean, it’s my hope that every man who has had to step down will be replaced by a woman. I’ve thought about this a lot—I think that certain changes have already taken place that enable these stories to finally get traction.

I think the legacy of Jill Abramson is women reporters who were assigned to a gender beat, and The New York Times now has a gender team, and it was the presence of those women who took down Harvey Weinstein. So I think in some ways the women are already in place in ways that have had a real impact and have helped these stories get traction.

Some of the issues will remain in 2018—paid leave, some of the things that we might have gotten traction on under a Hillary Clinton administration we’re probably not gonna get traction on under Donald Trump—for any kind of paid leave or paid child care plan. But the sexual harassment cascade I think is going to linger and I do think that we’ll see more men replaced by women.

We clearly are seeing more women running for office. I think the midterms this year are going to be really eye-opening, and I think we will bring more women to congress and that has an impact on women in the workplace. Then we’ll see more legislation. We’ve got the outrage now with the outcome of the presidential election, but I think the outrage will lead to more women in congress, and more women in congress will lead to movement on things like paid leave and childcare. But it’s gonna take a while.

Mia is reading The Atlantic’s The Sexes magazine.

Why do you think it took until now for the story to be told?

Because the women kept the secret—they were told during the war that if anybody asked them what they did they were to say that they were secretaries, that they sharpened pencils, and filled ink bottles, and emptied waste baskets. People believed them because they were women, so people believed that the work they were doing couldn’t possibly be important. In that sense they were the ideal intelligence officers.

This was intelligence that they were doing, it was also decryption, literally. It was decryption and cyber-security and hacking.

By the time histories and memoirs began to be written about World War II code breaking—books like The Imitation Game and any number of books, really thick books, about specific codebreaking, about the [Battle of] Midway—historians really neglected the women’s role.

In some of the books that I read, it would literally be mentioned in a parenthetical by a male historian: “Oh by the way, most of this work was done by women.” But they would make the assumption that the important work was actually being done by the men…

So you’re an expert on women at work. Where did 2017 leave us in this narrative?

I think one of the reasons that we’re still having these absurd conversations about whether women belong in the tech sector is because these secrets were kept and because women were written out of the history.

I mean, so much of our tech sector was born during World War II; the early computers that the army and the navy developed, which were our first computers, were developed to break codes or to calculate weapons’ trajectory. So the Army was working on ENIAC, the Navy was working on the Mark I computers that Grace Hopper was instrumental on working on. And the ENIAC was programmed by women.

All these women were being competed for during the war, but because their contributions were written out of history for so long, we still find ourselves arguing with people like James Damore over whether women are as well-suited as men to do this work, when, in fact, the field was pioneered by women. And then after the war, when it became clear that it was going to be huge and profitable, women were sent back home.

You wrote The Atlantic story “Why is Silicon Valley so Awful to Women” around the same time that Susan Fowler threw this topic wide open. Did you have any indication when you were writing that story that it was gonna become this huge?

That broke literally as my piece was going to press, and we were able to work in a reference to it in the printed piece, and then a bit more in the online version of the piece. But looking back at some of the reporting I did, and some of the women that I interviewed—specifically women involved in venture capital—and talking about the sexism and sexual harassment that they encountered, I put two and two together and realized that they were talking about the venture capitalists who were named and accused of sexual harassment not that long after the Susan Fowler memo.

What do you think are the trends we’ll face this year in terms of women at work? And what are some challenges?

Well, it sounds cliché to say this has been a watershed year. I mean, it’s my hope that every man who has had to step down will be replaced by a woman. I’ve thought about this a lot—I think that certain changes have already taken place that enable these stories to finally get traction.

I think the legacy of Jill Abramson is women reporters who were assigned to a gender beat, and The New York Times now has a gender team, and it was the presence of those women who took down Harvey Weinstein. So I think in some ways the women are already in place in ways that have had a real impact and have helped these stories get traction.

Some of the issues will remain in 2018—paid leave, some of the things that we might have gotten traction on under a Hillary Clinton administration we’re probably not gonna get traction on under Donald Trump—for any kind of paid leave or paid child care plan. But the sexual harassment cascade I think is going to linger and I do think that we’ll see more men replaced by women.

We clearly are seeing more women running for office. I think the midterms this year are going to be really eye-opening, and I think we will bring more women to congress and that has an impact on women in the workplace. Then we’ll see more legislation. We’ve got the outrage now with the outcome of the presidential election, but I think the outrage will lead to more women in congress, and more women in congress will lead to movement on things like paid leave and childcare. But it’s gonna take a while.

Mia is reading The Atlantic’s The Sexes magazine.