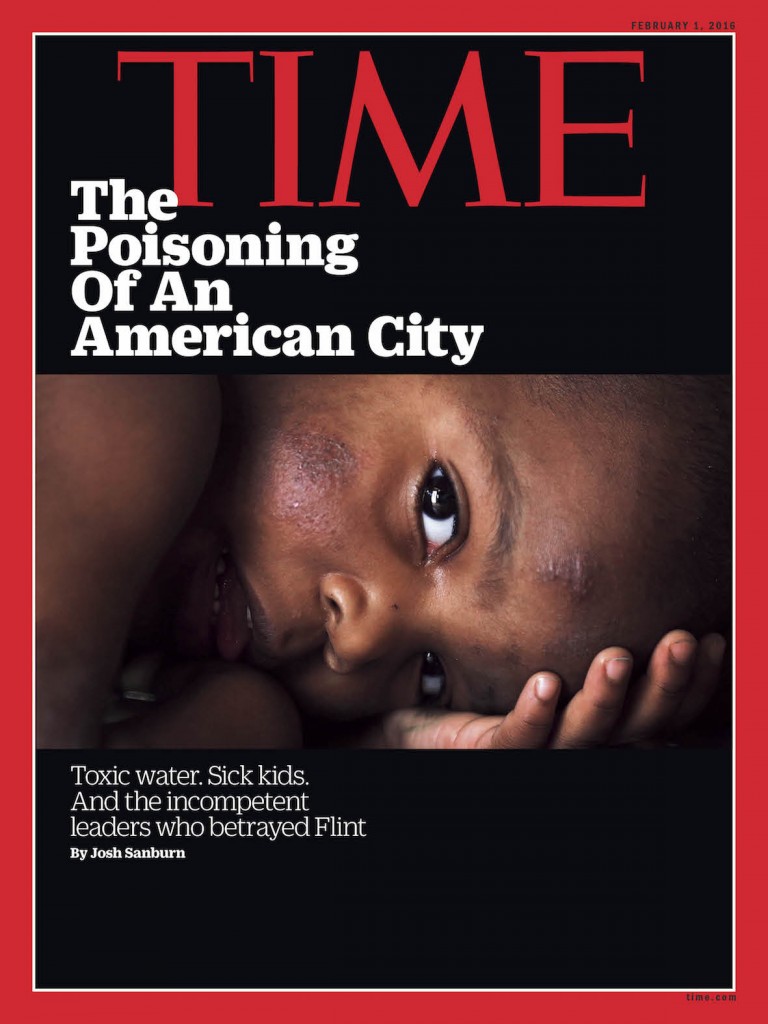

Story: “The Toxic Tap“

Outlet: TIME

Reporter: Josh Sanburn

TIME reporter Josh Sanburn experienced the anger felt by Flint water residents following the water crisis as he reported from the Michigan city for TIME’s cover story. Sanburn said residents are angry at politicians and bureaucrats who failed to stop the nearly two-year long crisis of contaminated water flowing from their faucets, but he said many residents believe Flint will rebound and that the crisis has brought the community together. Read more about what Sanburn experienced on the ground and what’s next for the city.

Can you describe the emotions felt by the Flint residents with whom you spoke?

Flint residents, by and large, are angry. Angry at their governor. Angry at city officials who told them the water was safe to drink despite reports to the contrary. Angry at the series of emergency managers who were appointed by the state to clean up Flint’s financial woes but put dollars ahead of the safety of city residents. Much of that anger comes from parents who simply turned on the tap and unwittingly served their children what amounted to poison. Lead exposure in kids age six and under can be devastating. If a Flint resident’s son or daughter appears to be doing poorly in school in a few years, has problems focusing, is showing signs of learning disabilities, those parents will always wonder: Maybe it was the water.

What most surprised you about the reality on the ground?

Two things. There are extremely high levels of poverty in Flint, and seeing it up close is a visceral reminder of the severity of this crisis. I visited one home where a family was barely getting by on the bottled water that had been donated to them. Many residents not only have incredibly high water bills—even as the water remains unsafe to drink—but they then can’t afford to regularly buy enough water to bathe in, cook with, and drink. Some of them only bathe their children once a week. The other surprising thing: There is a sizable portion of Flint residents who still believe in their city and believe that Flint will rebound even after the water crisis. A number of Flint residents told me that the recent problems have brought residents together in ways they’ve never seen before.

How did the situation get to this point?

How Flint’s water became poisoned is a tangle of events, but the basic story is this: A few years ago, Flint made the decision to stop purchasing water from Detroit and join a pipeline project called the Karegnondi Water Authority. The problem was that the pipeline wasn’t finished, so Flint needed a temporary water source and turned to the Flint River. When the city started pumping the river water into people’s homes, there was no corrosion control in place, meaning the city was not effectively treating the water. As the water flowed through the city’s lead service pipes, it ate away at them, carrying extremely high levels of lead into residences. State officials denied this was happening for months even though there were internal reports showing elevated lead levels in several Flint homes. It took outside researchers—notably Marc Edwards at Virginia Tech University and Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Hurley Medical Center in Flint—to eventually prod officials to acknowledge that, yes, there is lead in the water and it is not safe to drink.

Are the residents receiving the help and aid they need now?

They’re receiving some help, but it’s not enough. A number of residents I spoke to said that most of the water they were receiving was coming from donations, often from everyday people just trying to help. When the National Guard was first deployed, only seven members were sent to help a city of 100,000, and I only saw one of them when I was there. The White House has now pledged $80 million for Flint while the governor is asking the state legislature to approve $28 million. But that money will take a while to get to residents who are still struggling to pay the costs of constantly stocking up on safe water.

You write about the history of Flint and decline of manufacturing and the auto industry. Is the current situation a repercussion of that decline in some way(s)? If so, how?

Flint has been in decline for decades. It now has half the population it did in 1960, and much of that is due to General Motors packing up and leaving town. GM employed roughly 80,000 people in the Flint area in the 1950s. Today, it’s just a few thousand, and nothing has come in to fill that void. So the declining tax base means the city hasn’t been able to invest in the kinds of infrastructure or development projects that might help the city grow. That has led to budget deficits which led to emergency managers which led to decisions being made—like switching from Detroit water and not investing in corrosion control—purely to save money.

I know every tragedy is different, but did this situation remind you of another event in recent memory or in our history?

More than a decade ago, thousands of children were exposed to lead in Washington, D.C., which led to a Congressional investigation and, as it turns out, was discovered by Marc Edwards, the same corrosion expert who shed light on Flint’s water problems. There were the groundwater contamination issues in Hinkley, Calif., uncovered by activist Erin Brockovich. And then there are other instances of corporations polluting water sources, like the story of Dupont dumping toxic waste into a creek. The seriousness of the problems in Flint certainly rank up there with the most serious breaches involving water sources in the U.S.

Are the residents united to push for change? If so, what is the change they’re seeking?

By most accounts, they are. Many of them certainly want to see the governor resign because they believe he knew more about the situation than he’s letting on. The real change may have to come through a long-term, systematic investment in the city’s aging infrastructure, most notably the corroded lead service lines that connect residents’ homes to the main city water pipes.

What will the short and long-term repercussions be—in the city, state, nationally or in the minds and lives of those most hurt?

The long-term consequences are most importantly the developmental issues that many children potentially face from lead exposure. And it will take years for those effects to make themselves known. But there is also the problem of trust. It will be extraordinarily difficult for most residents to ever believe what their government tells them. Lee-Anne Walters, who was instrumental in hounding officials about lead showing up in her home, has since moved part-time to Virginia. She’s now hundreds of miles from Flint, and she still doesn’t drink water from the tap.

Learn more about how to help the Flint residents through several charities in this piece on Time.com. See more photos from the ground here and follow the Flint topic to keep up with the latest on the crisis.

~GabyS is reading the water topic

GET FLIPBOARD ON:

iOS / ANDROID / WINDOWS / WEB

FOLLOW US ON:

FLIPBOARD / TWITTER / INSTAGRAM / FACEBOOK / GOOGLE+ / TUMBLR / YOUTUBE / SOUNDCLOUD / PINTEREST / MEDIUM

Are the residents receiving the help and aid they need now?

They’re receiving some help, but it’s not enough. A number of residents I spoke to said that most of the water they were receiving was coming from donations, often from everyday people just trying to help. When the National Guard was first deployed, only seven members were sent to help a city of 100,000, and I only saw one of them when I was there. The White House has now pledged $80 million for Flint while the governor is asking the state legislature to approve $28 million. But that money will take a while to get to residents who are still struggling to pay the costs of constantly stocking up on safe water.

You write about the history of Flint and decline of manufacturing and the auto industry. Is the current situation a repercussion of that decline in some way(s)? If so, how?

Flint has been in decline for decades. It now has half the population it did in 1960, and much of that is due to General Motors packing up and leaving town. GM employed roughly 80,000 people in the Flint area in the 1950s. Today, it’s just a few thousand, and nothing has come in to fill that void. So the declining tax base means the city hasn’t been able to invest in the kinds of infrastructure or development projects that might help the city grow. That has led to budget deficits which led to emergency managers which led to decisions being made—like switching from Detroit water and not investing in corrosion control—purely to save money.

I know every tragedy is different, but did this situation remind you of another event in recent memory or in our history?

More than a decade ago, thousands of children were exposed to lead in Washington, D.C., which led to a Congressional investigation and, as it turns out, was discovered by Marc Edwards, the same corrosion expert who shed light on Flint’s water problems. There were the groundwater contamination issues in Hinkley, Calif., uncovered by activist Erin Brockovich. And then there are other instances of corporations polluting water sources, like the story of Dupont dumping toxic waste into a creek. The seriousness of the problems in Flint certainly rank up there with the most serious breaches involving water sources in the U.S.

Are the residents united to push for change? If so, what is the change they’re seeking?

By most accounts, they are. Many of them certainly want to see the governor resign because they believe he knew more about the situation than he’s letting on. The real change may have to come through a long-term, systematic investment in the city’s aging infrastructure, most notably the corroded lead service lines that connect residents’ homes to the main city water pipes.

What will the short and long-term repercussions be—in the city, state, nationally or in the minds and lives of those most hurt?

The long-term consequences are most importantly the developmental issues that many children potentially face from lead exposure. And it will take years for those effects to make themselves known. But there is also the problem of trust. It will be extraordinarily difficult for most residents to ever believe what their government tells them. Lee-Anne Walters, who was instrumental in hounding officials about lead showing up in her home, has since moved part-time to Virginia. She’s now hundreds of miles from Flint, and she still doesn’t drink water from the tap.

Learn more about how to help the Flint residents through several charities in this piece on Time.com. See more photos from the ground here and follow the Flint topic to keep up with the latest on the crisis.

~GabyS is reading the water topic

GET FLIPBOARD ON:

iOS / ANDROID / WINDOWS / WEB

FOLLOW US ON:

FLIPBOARD / TWITTER / INSTAGRAM / FACEBOOK / GOOGLE+ / TUMBLR / YOUTUBE / SOUNDCLOUD / PINTEREST / MEDIUM