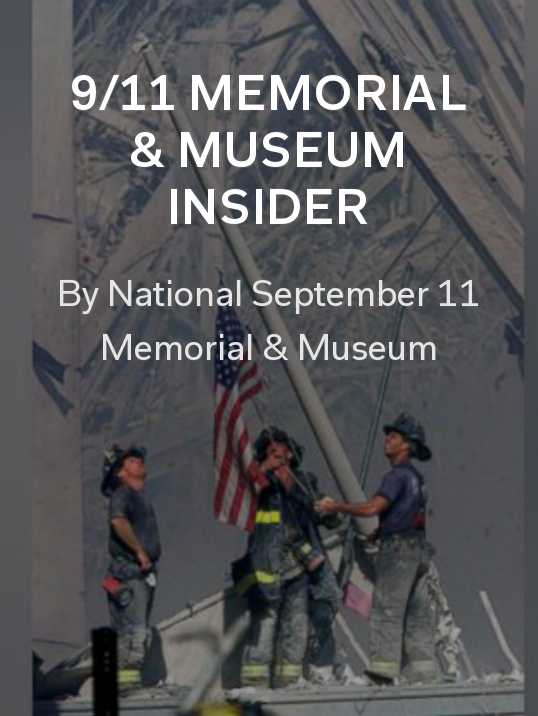

It was a cloudless and warm Tuesday morning in September, and Joe Daniels was running a little late. Normally, the McKinsey & Co. consultant would take the subway to his job in lower Manhattan, and walk in the shade of the Twin Towers. But today was anything but normal. When he climbed from the underground to the street, what he saw was a plume of smoke coming from the North Tower. Then he heard the sound of United Airlines Flight 175 as it slammed into the South Tower. We all remember what we were doing on Sept. 11, 2001. Daniels remembers fleeing on foot. He remembers seeing bodies fall from the towers. He saw a team of doctors waiting for trauma patients that never arrived. He eventually made it to his apartment in the West Village, and climbed to the roof in time to watch the second tower fall and fighter jets streak across the sky. It was unforgettable. Yet Daniels has made it his business to never forget: For the last eight years, he has dedicated himself to the National September 11 Memorial & Museum project, first as the organization’s general counsel, and now as its president. The memorial opened in 2011, and the museum opens next spring; both are sited at Ground Zero. We spoke to Daniels about the museum, 9/11 and the emotional toll the project has taken. His organization also created a magazine about the 9/11 memorial and museum, which you can browse by tapping on the cover below.

How do you hope people will respond to visiting Ground Zero? Fundamentally, it’s not a single response. We want people to be impacted and think about what they’ve experienced. For different ages that’s different things. For younger folk, it’s the notion that they see how people came together to take care of one another with limitless compassion. For a child, it’s the knowledge that, when the times require, we can help each other out. For everyone else, the older people, it’s complex. It’s that we live in the United States of America, although flawed, the best example of freedom that I think the world has ever known. What this museum will say in part is that freedom should not be taken for granted and that we have to defend our values and appreciate what we have because there are those out there who will kill themselves to take that away from us. What’s it been like building the museum tied to an event that is so pivotal in recent history? We’re laying out a very complicated story. I think people remember from that day the confusion because of the simultaneity of events in New York, the Pentagon and Flight 93. We want to organize that for people in a way that makes sense while bring out the human stories behind it. There are scores of artifacts and items that you can choose to display. What goes into choosing each artifact? We start with the principle that we only display artifacts that can help elucidate a part of the story of what actually happened. There’s a lot of visually interesting stuff out there, but when we showcase an artifact—for example, Engine 21—it’s there not because it looks interesting, which it does, it’s there because it represents a story—that of Captain Billy Burke. He was the captain who ordered his men out of the north tower to safety when he was aware that the south tower collapsed. Captain Burke stayed behind to try and help out co-workers Abe Zelmanowitz and Ed Beyea, a paraplegic. Unfortunately those three were killed. It’s emblematic of the sacrifices made by so many first responders: this was their life, this was their job, this is what they did. There’s been some controversy over the inclusion of the two-beam cross, which carries a heavy religious undertone. Why have you chosen to include it? It’s such an important part of this recovery period where people worked all day and night for nine months to help clean up and rebuild. And this cross was in the middle of the fires burning for 99 days—some of the most hellish conditions on earth. This cross that emerged from the pile provided some brief spirituality in the chaos of Ground Zero. What has it been like to revisit this topic, day in and day out, for the last eight years? There’s an emotional anchor, but I do think as with any human response, you can’t only occupy that emotional space. We have a job to do. We raised a lot of money. We have to create the museum’s exhibitions. It’s a complicated construction process. So there’s real tasks that we have to focus on which helps relieve the burden of the emotionality. But at the same time we’re anchored back to that day. How do you hope to tell this narrative that you’re building in the museum to broader audiences? We definitely have been taking full advantage of digital channels; our Flipboard magazine is one example of that and we’ll continue to do that because the reach of it is so wide. At the end of the day I firmly believe people need to come here. There’s something very powerful about stepping on the grounds of the memorial and eventually entering the museum. This is a place that people have in their minds. They remember the towers standing tall, defining the New York City skyline. They remember 9/11, the attack, the buildings collapsing, the pile, the smoke that burned and the empty pit that was there for many years. So despite the digital-ness of this world, we still need people to come here and visit this sacred place. Has it been too soon to build a museum, let alone a memorial? Frankly, I appreciate that perspective. Most people have said, ‘What took so long?’ When you look at other major events in any way analogous to this, whether it’s war or something else, it takes a lot longer and it provides a lot more breathing room. I think the issue here is the attack happened basically in the middle of NYC and left a hole. That also left a desire, partly by our political leaders, to getting it done right away because you have a wound in your city. I think there needs a period to go by, but I do think 10 years is the right time for the memorial. What do you think is the lesson to be taken from 9/11? It’s about not taking for granted the freedoms that we have: our ability to say what we want, to practice our religion, to have freedom of speech. Those are precious liberties that we need to be cognizant of given all those who had to die, or those who sacrificed themselves so we can be free. It’s important to remember that we can fight and debate and argue and be partisan—because at the end of the day, we’re all Americans. ~NajibA /flipboard @flipboard +flipboard